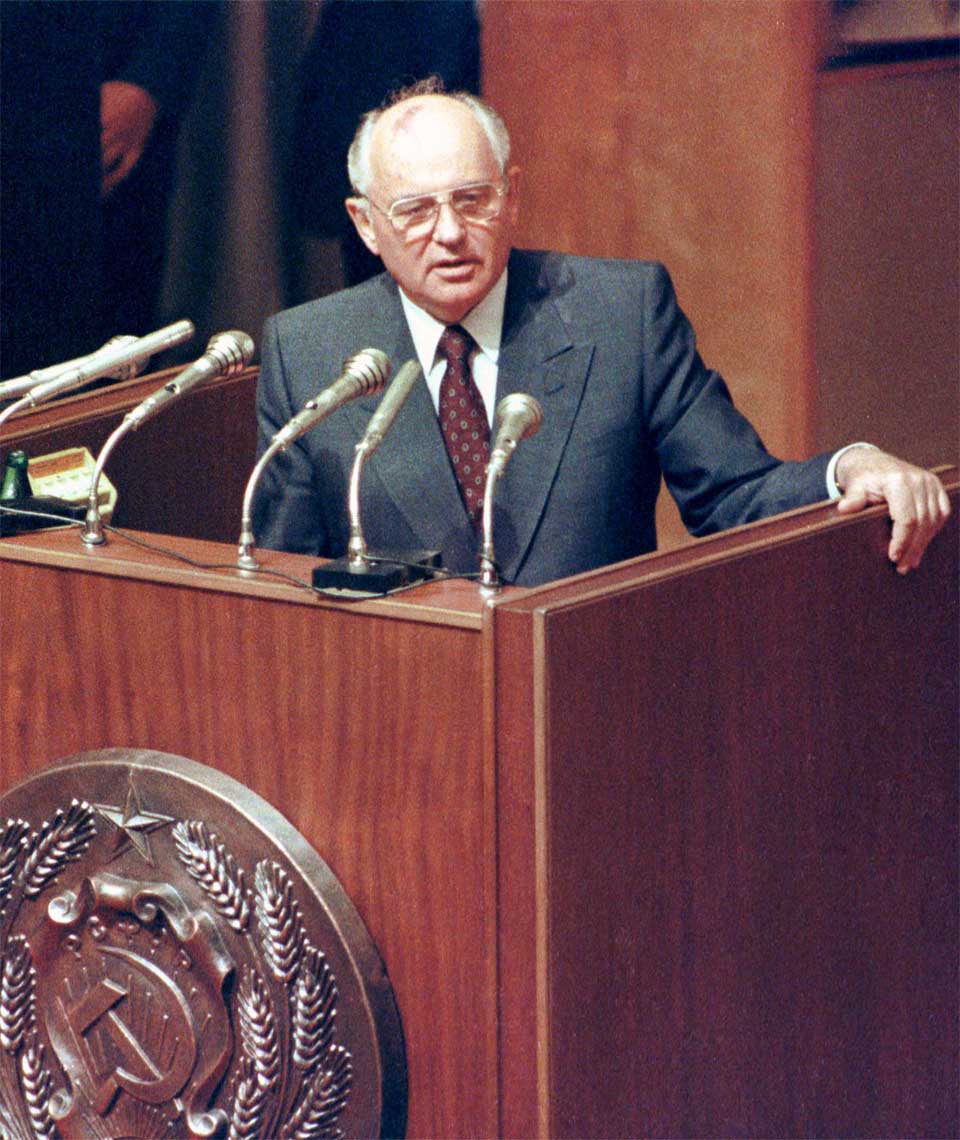

It is hard to imagine that anyone could have dismantled the Soviet Union from the inside faster or more comprehensively than Mikhail Gorbachev, a man who had no such intention. Its crumbling is both Gorbachev’s singular achievement and his personal tragedy.

It is also the most important moment in history since 1945.

Popular perceptions have transformed the former Soviet leader into a kitschy icon, remembered as much for starring in an advert for no-crust pizza, as for picking up a Nobel Peace Prize.

But in the demise of ‘The Evil Empire’ he was no naïf, nor a catalyst for generic historic inevitabilities. Almost every single event in the countdown to the fall of communism in Russia and beyond is a direct reflection of the ideals, actions and foibles of Mikhail Gorbachev and those he confronted or endorsed.

This is the story of a farm mechanic who managed to penetrate the inner sanctum of the world’s biggest country, an explanation of what drove him once he reached the top, and an attempt to understand whether he deserves opprobrium or sympathy, ridicule or appreciation.

RIA Novosti.

RIA Novosti.

If not me, who? And if not now, when?

— Mikhail Gorbachev

CHILDHOOD

Growing up a firebrand Communist among Stalin’s purges

Born in 1931 in a Ukrainian-Russian family in the village of Privolnoye in the fertile Russian south, Mikhail Gorbachev’s childhood was punctuated by a series of almost Biblical ordeals, albeit those shared by millions of his contemporaries.

His years as a toddler coincided with Stalin’s policy of collectivization – the confiscation of private lands from peasants to form new state-run farms – and Stavropol, Russia’s Breadbasket, was one of the worst-afflicted. Among the forcible reorganization and resistance, harvests plummeted and government officials requisitioned scarce grain under threat of death.

Gorbachev later said that his first memory is seeing his grandfather boiling frogs he caught in the river during the Great Famine.

Yet another grandfather, Panteley – a former landless peasant — rose from poverty to become the head of the local collective farm. Later Gorbachev attributed his ideological make-up largely to his grandfather’s staunch belief in Communism “which gave him the opportunity to earn everything he had.”

Panteley’s convictions were unshaken even when he was arrested as part of Stalin’s Great Purge. He was accused of joining a “counter-revolutionary Trotskyite movement” (which presumably operated a cell in their distant village) but returned to his family after 14 months behind bars just in time for the Second World War to break out.

Just in time for the Second World War to break out. For much of the conflict, the battle lines between the advancing Germans and the counter-attacking Red Army stretched across Gorbachev’s homeland; Mikhail’s father was drafted, and even reported dead, but returned with only shrapnel lodged in his leg at the end of the war.

Although Sergey was a distant presence in his son’s life up to then and never lived with him, he passed on to Mikhail a skill that played a momentous role in his life — that of a farm machinery mechanic and harvester driver. Bright by all accounts, Mikhail quickly picked up the knack — later boasting that he could pick out any malfunction just by the sound of the harvester or the tractor alone.

But this ability was unlikely to earn him renown beyond his village. Real acclaim came when the father and son read a new decree that would bestow a national honor on anyone who threshed more than 8000 quintals (800 tons or more than 20 big truckloads) of grain during the upcoming harvest. In the summer of 1948 Gorbachev senior and junior ground an impressively neat 8888 quintals. As with many of the agricultural and industrial achievements that made Soviet heroes out of ordinary workers, the exact details of the feat – and what auxiliary efforts may have made it possible – are unclear, but 17-year-old Gorbachev became one of the youngest recipients of the prestigious Order of the Red Banner of Labor in its history.

Having already been admitted to the Communist Party in his teen years (a rare reward given to the most zealous and politically reliable) Mikhail used the medal as an immediate springboard to Moscow. The accolade for the young wheat-grinder meant that he did not have to pass any entrance exams or even sit for an interview at Russia’s most prestigious Moscow State University.

With his village school education, Gorbachev admitted that he initially found the demands of a law degree, in a city he’d never even visited before, grueling. But soon he met another ambitious student from the countryside, and another decisive influence on his life. The self-assured, voluble Raisa, who barely spent a night apart from her husband until her death, helped to bring out the natural ambition in the determined, but occasionally studious and earnest Gorbachev. Predictably, Gorbachev rose to become one of the senior figures at the university’s Komsomol, the Communist youth league — which with its solemn group meetings and policy initiatives served both as a prototype and the pipeline for grown-up party activities.

STAVROPOL

Party reformist flourishes in Khruschev’s Thaw

Upon graduation in 1955, Gorbachev lasted only ten days back in Stavropol’s prosecutor’s office (showing a squeamishness dealing with the less idealistic side of the Soviet apparatus) before running across a local Komsomol official. For the next 15 years his biography reads like a blur of promotions – rising to become Stavropol region’s top Komsomol bureaucrats, overseeing agriculture for a population of nearly 2.5 million people before his 40th birthday.

All the trademarks of Gorbachev’s leadership style, which later became famous around the world, were already in evidence here. Eschewing Soviet officials’ habit of barricading themselves inside the wood-paneled cabinets behind multiple receptions, Gorbachev spent vast swathes of his time ‘in the field’, often literally in a field. With his distinctive southern accent, and his genuine curiosity about the experiences of ordinary people, the young official a struck chord as he toured small villages and discussed broken projectors at local film clubs and shortages of certain foodstuffs.

His other enthusiasm was for public discussion, particularly about specific, local problems – once again in contrast with the majority of officials, who liked to keep negative issues behind closed doors. Gorbachev set up endless discussion clubs and committees, almost quixotically optimistic about creating a better kind of life among the post-war austerity.

POLITBURO

Cutting the line to the throne

By the 1970s any sign of modernization in Soviet society or leadership was a distant memory, as the country settled into supposed “advanced socialism”, with the upheavals and promises of years past replaced by what was widely described as ‘An Era of Stagnation’ (the term gained official currency after being uttered by Gorbachev himself in one of his early public speeches after ascending to the summit of the Soviet system).

Without Stalin’s regular purges, and any democratic replacement mechanisms, between the mid-1960s and 1980s, almost the entire apparatus of Soviet leadership remained unchanged, down from the increasingly senile Leonid Brezhnev, who by the end of his life in 1982 became a figure of nationwide mockery and pity, as he slurred through speeches and barely managed to stand during endless protocol events, wearing gaudy carpets of military honors for battles he never participated in. Predictably, power devolved to the various factions below, as similarly aged heavyweights pushed their protégés into key positions.

RIA Novosti.

Mikhail Andreyevich Suslov, CPSU CC Politbureau member, CPSU CC secretary, twice Hero of Socialist Labor.

RIA Novosti.Leonid Brezhnev, left, chairman of the USSR Supreme Soviet Presidium and general secretary of the CPSU Central Committee, with Alexei Kosygin, chairman of the USSR Council of Ministers, on Lenin’s Mausoleum on May 1, 1980.

RIA Novosti.The Soviet Communist Party’s politburo member Konstantin Chernenko and central committee member Yury Andropov attend the Kremlin Palace of Congresses’ government session dedicated to the 60th anniversary of the USSR.

RIA Novosti.Yuri Andropov (1914-1984), General Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee (since November 1982).

RIA Novosti.

With a giant country as the playground, the system rewarded those who came up with catchy programs and slogans, took credit for successes and steered away from failures, and networked tirelessly to build up support above and below. Gorbachev thrived here. His chief patrons were Brezhnev himself, purist party ideologue Mikhail Suslov, who considered Stavropol his powerbase, and most crucially the hardline head of the KGB, Yuri Andropov. The security chief referred to the aspiring politician as ‘My Stavropol Rough Diamond’ — another rejoinder to those seeking to paint Gorbachev as a naïve blessed outsider, a Joan of Arc of the Soviet establishment.

After being called to Moscow in 1978 to oversee Soviet agriculture — an apocryphal story suggests that he nearly missed out on the appointment when senior officials couldn’t find him after he got drunk celebrating a Komsomol anniversary, only to be rescued by a driver at the last moment — Mikhail Gorbachev was appointed to the Politburo in 1980.

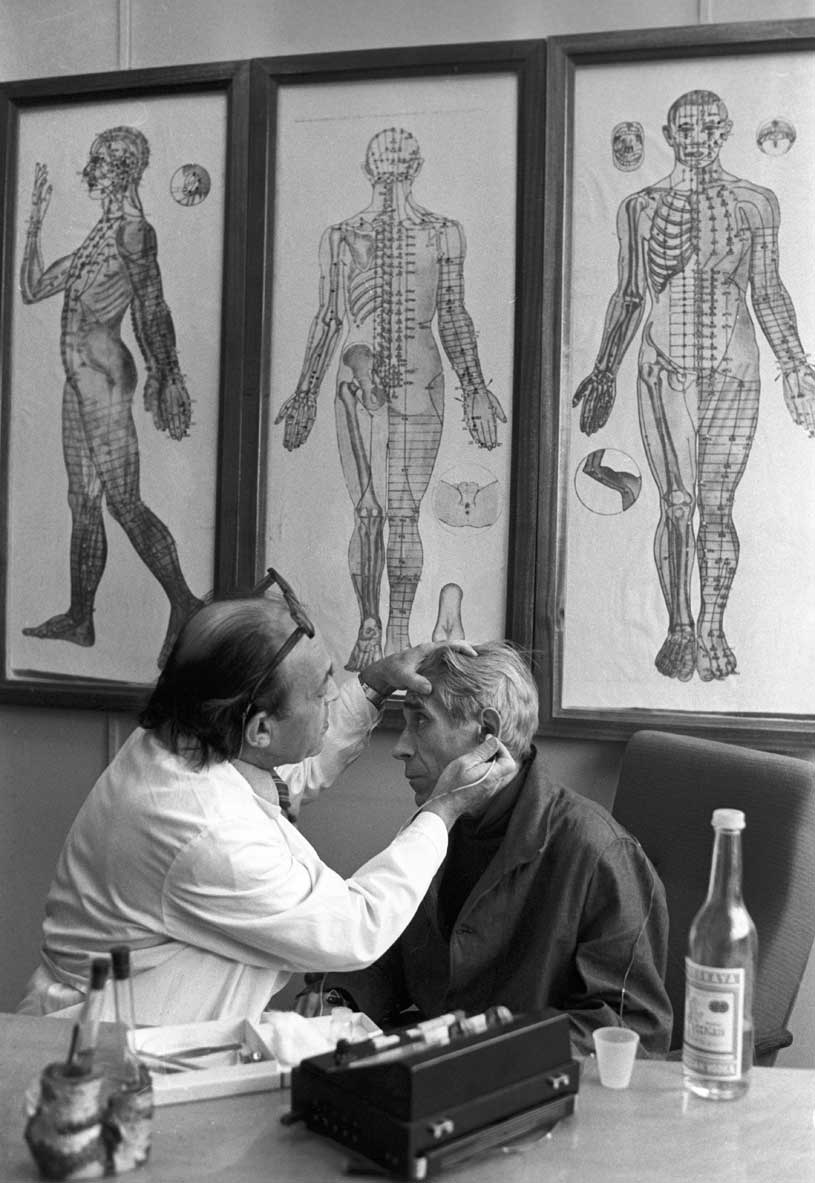

The Politburo, which included some but not all of the ministers and regional chiefs of the USSR, was an inner council that took all the key decisions in the country, with the Soviet leader sitting at the top of the table, holding the final word (though Brezhnev sometimes missed meetings or fell asleep during them). When Gorbachev became a fully-fledged member he was short of his 50th birthday. All but one of the dozen other members were over sixty, and most were in their seventies. To call them geriatric was not an insult, but a literal description of a group of elderly men – many beset by chronic conditions far beyond the reach of Soviet doctors – that were more reminiscent of decrepit land barons at the table of a feudal king than effective bureaucrats. Even he was surprised by how quickly it came.

Brezhnev, who suffered from a panoply of circulation illnesses, died of a heart attack in 1982. Andropov, who was about to set out on an energetic screw-tightening campaign, died of renal failure in 1984. Konstantin Chernenko was already ill when he came to leadership, and died early in 1985 of cirrhosis. The tumbling of aged sovereigns, both predictable and tragicomic in how they reflected on the leadership of a country of more than 250 million people, not only cleared the path for Gorbachev, but strengthened the credentials of the young, energetic pretender.

RIA Novosti.

The decorations of General Secretary of the CPSU Leonid Brezhnev seen during his lying-in-state ceremony at the House of Unions.

RIA Novosti.Mikhail Gorbachev, the first and the last Soviet president (second left in the foreground) attending the funeral of General Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee Konstantin Chernenko (1911-1985) in Moscow’s Red Square.

RIA Novosti.The funeral procession during the burial of Leonid Brezhnev, general secretary of the CPSU central committee, chairman of the Presidium of the USSR Supreme Soviet.

RIA Novosti.The funeral of Yuri Andropov, General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR. The coffin is placed on pedestal near the Mausoleum on Red Square.

RIA Novosti.The funeral procession for General Secretary of the CPSU Konstantin Chernenko moving towards Red Square.

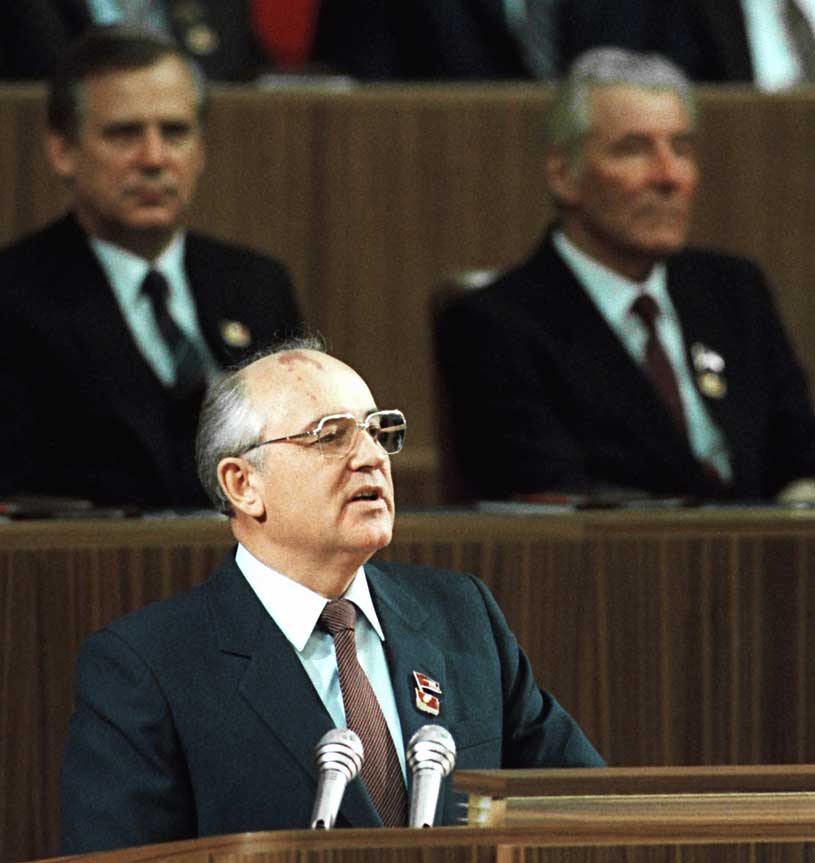

RIA Novosti.General Secretary of the Central Comittee of CPSU Mikhail Gorbachev at the tribune of Lenin mausoleum during May Day demonstration, Red square.

RIA Novosti.

On 11 March 1985, Gorbachev was named the General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the USSR.

REFORMS NEEDED

Overcoming economic inefficiency with temperance campaigns

As often in history, the reformer came in at a difficult time. Numbers showed that economic growth, which was rampant as Russia industrialized through the previous four decades, slowed down in Brezhnev’s era, with outside sources suggesting that the economy grew by an average of no more than 2 percent for the decade.

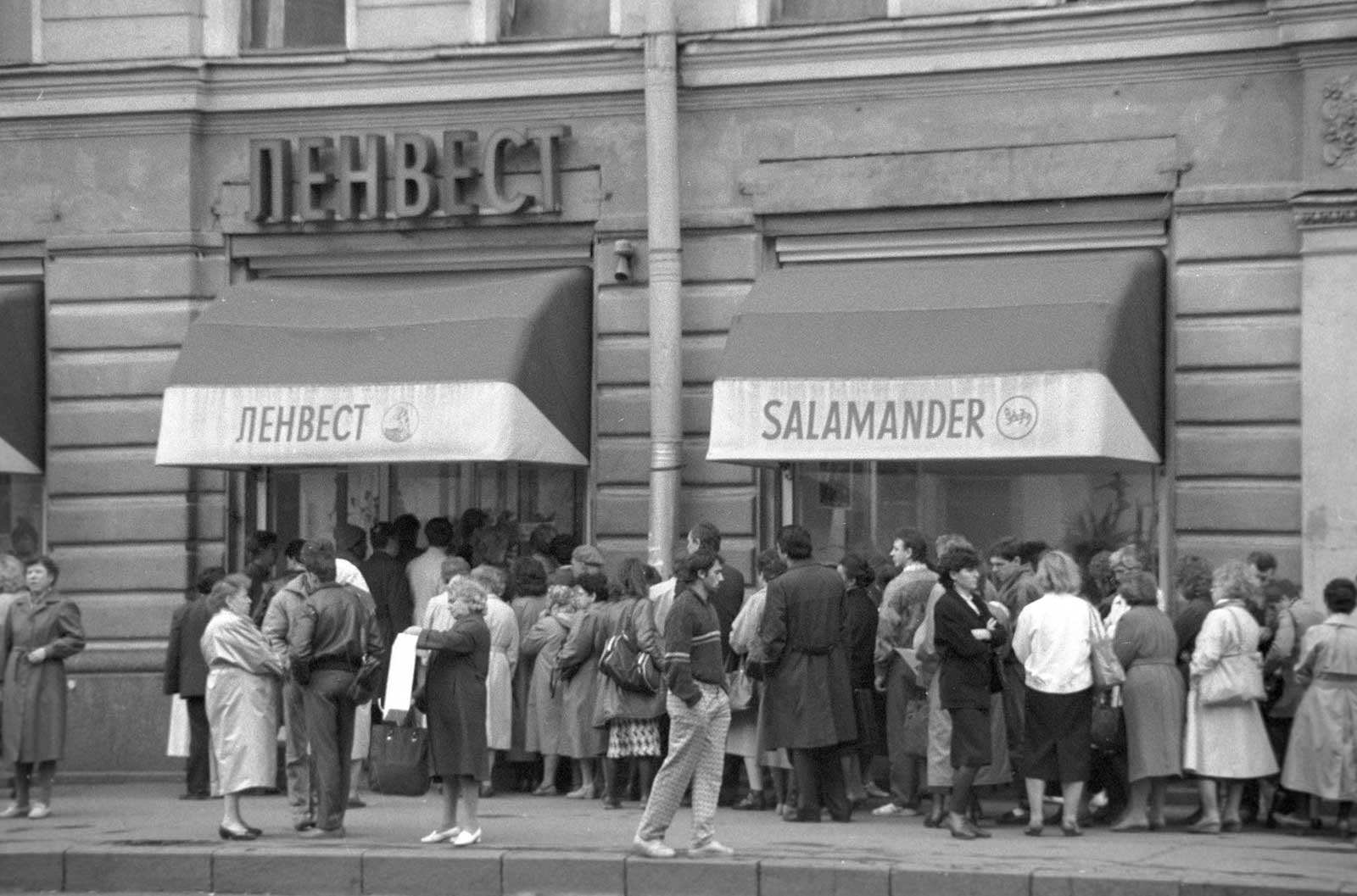

The scarcity of the few desirable goods produced and their inefficient distribution meant that many Soviet citizens spent a substantial chunk of their time either standing in queues or trading and obtaining things as ordinary as sugar, toilet paper or household nails through their connections, either “under the counter” or as Party and workplace perks, making a mockery of Communist egalitarianism. The corruption and lack of accountability in an economy where full employment was a given, together with relentless trumpeting of achievement through monolithic newspapers and television programs infected private lives with doublethink and cynicism.

Ria Novosti.

But this still does not describe the drab and constraining feel of the socialist command economy lifestyle, not accidentally eschewed by all societies outside of North Korea and Cuba in the modern world. As an example, but one central to the Soviet experience: while no one starved, there was a choice of a handful of standardized tins — labeled simply salmon, or corned beef — identical in every shop across the country, and those who were born in 1945 could expect to select from the same few goods until the day they died, day-in, day-out. Soviets dressed in the same clothes, lived in identical tower block housing, and hoped to be issued a scarce Lada a decade away as a reward for their loyalty or service. Combined with the lack of personal freedoms, it created an environment that many found reassuring, but others suffocating, so much so that a trivial relic of a different world, stereotypically a pair of American jeans, or a Japanese TV, acquired a cultural cachet far disproportionate to its function. Soviets could not know the mechanisms of actually living within a capitalist society — with its mortgages, job markets, and bills — but many felt that there were gaudier, freer lives being led all around the world.

And though it brought tens of millions of people out of absolute poverty, there was no longer an expectation that the lifestyles of ordinary Soviets would significantly improve whether a year or a decade into the future, and promise of a better future was always a key tenet of communism.

Several wide-ranging changes were attempted, in 1965 and 1979, but each time the initial charge was wound down into ineffectual tinkering as soon as the proposed changed encroached on the fundamentals of the Soviet regime — in which private commercial activity was forbidden and state control over the economy was total and centralized.

Ria Novosti.

Gorbachev deeply felt the malaise, and displayed immediate courage to do what is necessary — sensing that his reforms would not only receive support from below, but no insurmountable resistance from above. The policy of Uskorenie, or Acceleration, which became one of the pillars of his term, was announced just weeks after his appointment — it was billed as an overhaul of the economy.

But it did not address the fundamental structural inefficiencies of the Soviet regime. Instead it offered more of the same top-down administrative solutions — more investment, tighter supervision of staff, less waste. Any boost achieved through rhetoric and managerial dress-downs sent down the pyramid of power was likely to be inconsequential and peter out within months.

His second initiative, just two months after assuming control, betrayed these very same well-meaning but misguided traits. With widespread alcohol consumption a symptom of late-Soviet decline, Gorbachev devised a straightforward solution — lowering alcohol production and eventually eradicating drinking altogether.

RIA Novosti

RIA Novosti.

“Women write to me saying that children see their fathers again, and they can see their husbands,” said Gorbachev when asked about whether the reform was working.

Opponents of the illiberal measure forced Russian citizens into yet more queues, while alcoholics resorted to drinking industrial fluids and aftershave. Economists said that the budget, which derived a quarter of its total retail sales income from alcohol, was severely undermined. Instead a shadow economy sprung up — in 1987, 500 thousand people were arrested for engaging in it, five times more than just two years earlier.

More was needed, and Gorbachev knew it.

PERESTROIKA

“We must rebuild ourselves. All of us!”

Gorbachev at his zenith

Gorbachev first uttered the word perestroika — reform, or rebuilding — in May 1986, or rather he told journalists, using the characteristic and endearing first-person plural, “We must rebuild ourselves. All of us!” Picked up by reporters, within months the phrase became a mainstay of Gorbachev’s speeches, and finally the symbol of the entire era.

Before his reforms had been chiefly economic and within the existing frameworks; now they struck at the political heart of the Soviet Union.

The revolution came from above, during a long-prepared central party conference blandly titled “On Reorganization and the Party’s Personnel Policy” on January 27, 1987.

In lieu of congratulatory platitudes that marked such occasions in past times, Gorbachev cheerfully delivered the suspended death sentence for Communist rule in the Soviet Union (much as he didn’t suspect it at the time).

“The Communist Party of the Soviet Union and its leaders, for reasons that were within their own control, did not realize the need for change, understand the growing critical tension in the society, or develop any means to overcome it. The Communist Party has not been able to take full advantage of socialist society,”

said the leader to an audience that hid its apprehension.

“The only way that a man can order his house, is if he feels he is its owner. Well, a country is just the same,” came Gorbachev’s trademark mix of homely similes and grand pronouncements.” Only with the extension of democracy, of expanding self-government can our society advance in industry, science, culture and all aspects of public life.”

“For those of you who seem to struggle to understand, I am telling you: democracy is not the slogan, it is the very essence of Perestroika.”

Gorbachev used the word ‘revolution’ eleven times in his address, anointing himself an heir to Vladimir Lenin. But what he was proposing had no precedent in Russian or Soviet history.

The word democracy was used over 70 times in that speech alone.

The Soviet Union was a one-party totalitarian state, which produced 99.9 percent election results with people picking from a single candidate. Attempts to gather in groups of more than three, not even to protest, were liable to lead to arrest, as was any printed or public political criticism, though some dissidents were merely subjected to compulsory psychiatric care or forced to renounce their citizenship. Millions were employed either as official KGB agents, or informants, eavesdropping on potentially disloyal citizens. Soviet people were forbidden from leaving the country, without approval from the security services and the Party. This was a society operated entirely by those in power, relying on compliance and active cooperation in oppression from a large proportion of the population. So, the proposed changes were a fundamental reversal of the flows of power in society.

RIA Novosti.

Between Gorbachev’s ascent and by the end of that year, two thirds of the Politburo, more than half of the regional chiefs and forty percent of the membership of the Central Committee of Communist Party, were replaced.

Gorbachev knew that democracy was impossible without what came to be known as glasnost, an openness of public discussion.

“We are all coming to the same conclusion — we need glasnost, we need criticism and self-criticism. In our country everything concerns the people, because it is their country,”

said Gorbachev, cunningly echoing Lenin, at that January forum, though the shoots of glasnost first emerged the year before.

From the middle of 1986 until 1987 censored Soviet films that lay on the shelves for years were released, the KGB stopped jamming the BBC World Service and Voice of America, Nobel Peace Prize winner nuclear physicist Andrei Sakharov and hundreds of other dissidents were set free, and archives documenting Stalin-era repressions were opened.

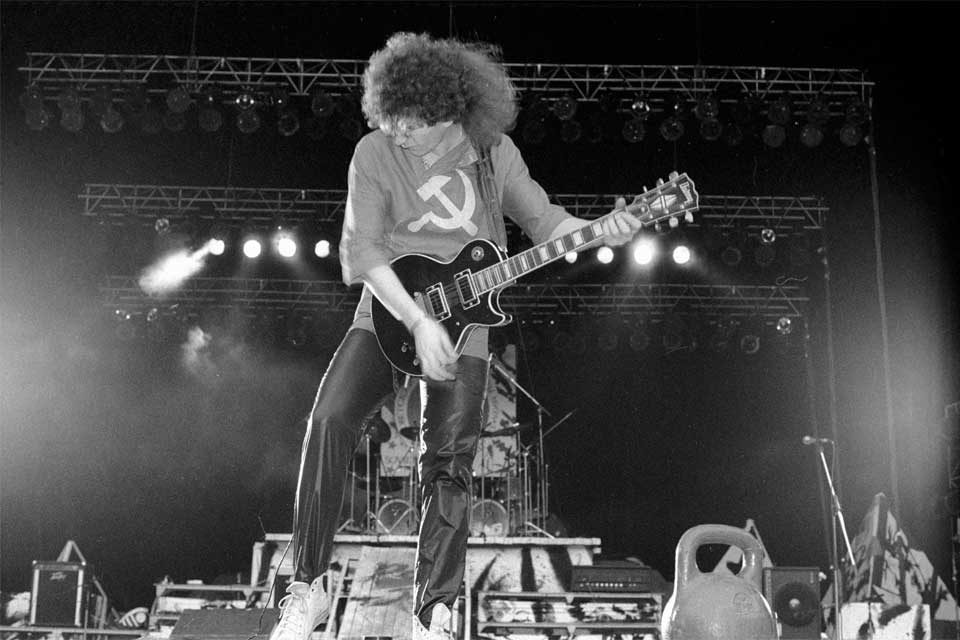

A social revolution was afoot. Implausibly, within two years, television went from having no programs that were unscripted, to Vzglyad, a talk show anchored by 20 and 30-somethings (at a time when most Soviet television presented were fossilized mannequins) that discussed the war in Afghanistan, corruption or drugs with previously banned videos by the Pet Shop Boys or Guns N’ Roses as musical interludes. For millions watching Axl Rose, cavorting with a microphone between documentaries about steel-making and puppet shows, created cognitive dissonance that verged on the absurd. As well as its increasing fascination with the West, a torrent of domestic creativity was unleashed. While much of what was produced in the burgeoning rock scene and the liberated film making industry was derivative, culturally naïve and is now badly dated, even artifacts from the era still emanate an unmistakable vitality and sincerity.

RIA Novosti.

“Bravo!” Poster by Svetlana and Alexander Faldin. Allegorically portraying USSR President Mikhail Gorbachev, it appeared at the poster exposition, Perestroika and Us.

RIA Novosti.Mikhail Gorbachev, General Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee and Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR, talking to reporters during a break between sessions. The First Congress of People’s Deputies of the USSR (May 25 — June 9, 1989). The Kremlin Palace of Congresses.

RIA Novosti.

Many welcomed the unprecedented level of personal freedom and the chance to play an active part in their own country’s history, others were alarmed, while others still rode the crest of the wave when swept everything before it, only to renounce it once it receded. But it is notable that even the supposed staunchest defenders of the ancien régime — the KGB officers, the senior party members — who later spent decades criticizing Perestroika, didn’t step in to defend Brezhnev-era Communism as they saw it being demolished.

What everyone might have expected from the changes is a different question — some wanted the ability to travel abroad without an exit visa, others the opportunity to earn money, others still to climb the political career ladder without waiting for your predecessor die in office. But unlike later accounts, which often presented Gorbachev as a stealthy saboteur who got to execute an eccentric program, at the time, his support base was broad, and his decisions seemed encouraging and logical.

As a popular politician Gorbachev was reaching a crescendo. His trademark town hall and factory visits were as effective as any staged stunts, and much more unselfconscious. The contrast with the near-mummified bodies of the previous General Secretaries — who, in the mind of ordinary Soviet citizens, could only be pictured on top of Lenin’s Mausoleum during a military parade, or staring from a roadside placard, and forever urging greater productivity or more intense socialist values — was overwhelming.

Gorbachev was on top — but the tight structure of the Soviet state was about to loosen uncontrollably.

RIA Novosti.

USSR president Mikhail Gorbachev visits Sverdlovsk region. Mikhail Gorbachev visiting Nizhnij Tagil integrated iron-and-steel works named after V.I. Lenin.

RIA Novosti.CPSU Central Committee General Secretary, USSR Supreme Soviet Presidium Chairman Mikhail Gorbachev in the Ukrainian SSR. Mikhail Gorbachev, second right, meeting with Kiev residents.

RIA Novosti.

COLD WAR ENDS

Concessions from a genuine pacifist

In the late 1980s the world appeared so deeply divided into two camps that it seemed like two competing species were sharing the same planet. Conflicts arose constantly, as the US and the USSR fought proxy wars on every continent — in Nicaragua, Angola and Afghanistan, with Europe divided by a literal battle line, both sides constantly updated battle plans and moved tank divisions through allied states, where scores of bases housed soldier thousands of miles away from home. Since the Cold War did not end in nuclear holocaust, it has become conventional to describe the two superpowers as rivals, but there was little doubt at the time that they were straightforward enemies.

“The core of New Thinking is the admission of the primacy of universal human values and the priority of ensuring the survival of the human race,” Gorbachev wrote in his Perestroika manifesto in 1988.

At the legendary Reykjavik summit in 1986, which formally ended in failure but in fact set in motion the events that would end the Cold War, both sides were astonished at just how much they could agree on, suddenly flying through agendas, instead of fighting pitched battles over every point of the protocol.

“Humanity is in the same boat, and we can all either sink or swim.”

RIA Novosti.

Landmark treaties followed: the INF agreement in 1987, banning intermediate ballistic missiles, the CFE treaty that reduced the military build-up in Europe in 1990, and the following year, the START treaty, reducing the overall nuclear stockpile of those countries. The impact was as much symbolic as it was practical — the two could still annihilate each other within minutes — but the geopolitical tendency was clear.

President Reagan: Signing of the INF Treaty with Premier Gorbachev, December 8, 1987

RIA Novosti.

RIA Novosti.

Military analysts said that each time the USSR gave up more than it received from the Americans. The personal dynamic between Reagan — always lecturing “the Russians” from a position of purported moral superiority, and Gorbachev — the pacifist scrambling for a reasonable solution, was also skewed in favor of the US leader. But Gorbachev wasn’t playing by those rules.

“Any disarmament talks are not about beating the other side. Everyone has to win, or everyone will lose,” he wrote.

The Soviet Union began to withdraw its troops and military experts from conflicts around the world. For ten years a self-evidently unwinnable war waged in Afghanistan ingrained itself as an oppressive part of the national consciousness. Fifteen thousand Soviet soldiers died, hundreds of thousands more were wounded or psychologically traumatized (the stereotypical perception of the ‘Afghan vet’ in Russia is almost identical to that of the ‘Vietnam vet’ in the US.) When the war was officially declared a “mistake” and Soviet tanks finally rolled back across the mountainous border in 1989, very few lamented the scaling back of the USSR’s international ambitions.

RIA Novosti.

Driver T. Eshkvatov during the final phase of the Soviet troop pullout from Afghanistan.

RIA Novosti.Soviet soldiers back on native soil. The USSR conducted a full pullout of its limited troop contingent from Afghanistan in compliance with the Geneva accords.

RIA Novosti.The convoy of Soviet armored personnel vehicles leaving Afghanistan.

RIA Novosti.

In July 1989 Gorbachev made a speech to the European Council, declaring that it is “the sovereign right of each people to choose their own social system.” When Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceausescu, soon to be executed by his own people, demanded — during the 40th anniversary of the Communist German Democratic Republic in October 1989 — that Gorbachev suppress the wave of uprisings, the Soviet leader replied with a curt “Never again!”

“Life punishes those who fall behind the times,” he warned the obdurate East German leader Erich Honecker. Honecker died in exile in Chile five years later, having spent his dying years fending off criminal charges backed by millions of angry Germans.

Russian tanks did pass through Eastern Europe that year — but in the other direction, as the Soviet Union abandoned its expensive bases that were primed for a war that neither side now wanted.

RIA Novosti.

Reuters.

Reuters.

By the time the Berlin Wall was torn down in November, Gorbachev was reportedly not even woken up by his advisors, and no emergency meetings took place. There was no moral argument for why the German people should not be allowed to live as one nation, ending what Gorbachev himself called the “unnatural division of Europe”. The quote came from his 1990 Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech.

ETHNIC TENSIONS

Smoldering ethnic conflicts on USSR’s outskirts flare up

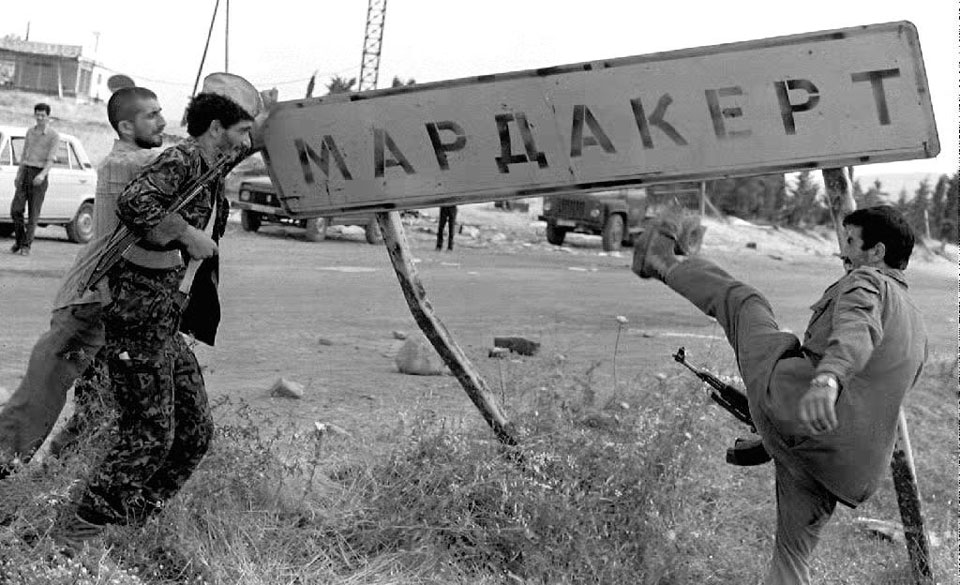

Ethnic tensions on the outskirts of the empire lead to full-scale wars after USSR’s collapse. Towards the end of his rather brief period as a Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev had to face a problem many thought of as done and dusted; namely, ethnic strife, leading to conflict and death.

By the mid-1980s, the Soviet Union was officially considered by party ideologists to be one multi-ethnic nation, despite it being comprised of 15 national republics and even more internal republics and regions, with dozens of ethnic groups living there in a motley mixture. The claim was not completely unfounded as the new generation all across the country spoke Russian and had basic knowledge of Russian culture along with Marxist philosophy. In fact, the outside world confirmed this unity by calling all Soviet citizens “Russians” — from Finno-Ugric Estonians in the West to the Turkic and Iranian peoples of Central Asia and natives of the Far East, closely related to the American Indians of Alaska.

RIA Novosti.

At the same time, the concept of the single people was enforced by purely Soviet methods — from silencing any existing problems in the party-controlled mass media, to ruthless suppression of any attempt of nationalist movements, and summary forced resettlement of whole peoples for “siding with the enemy” during WWII.

After Gorbachev announced the policies of Glasnost and democratization, many ethnic groups started to express nationalist sentiments. This was followed by the formation or legalization of nationalist movements, both in national republics and in Russia itself, where blackshirts from the “Memory” organization blamed Communists and Jews for oppressing ethnic Russians and promoted “liberation.”

Neither society nor law enforcers were prepared for such developments. The Soviet political system remained totalitarian and lacked any liberal argument against nationalism. Besides, the concept of “proletarian internationalism” was so heavily promoted that many people started to see nationalism as part of a struggle for political freedoms and market-driven economic prosperity. At the same time, the security services persisted in using the crude Soviet methods that had already been denounced by party leaders; police had neither the tools nor the experience for proper crowd control.

As a result, potential conflicts were brewing all across the country and the authorities did almost nothing to prevent them. In fact, many among the regional elites chose to ride the wave of nationalism to obtain more power and settle old accounts. At the same time, the level of nationalism was highly uneven and its manifestations differed both in frequency and intensity across the USSR.

In February 1988, Gorbachev announced at the Communist Party’s plenum that every socialist land was free to choose its own societal systems. Both Nationalists and the authorities considered this a go-ahead signal. Just days after the announcement, the conflict in the small mountain region of Nagorno-Karabakh entered an open phase.

Nagorno-Karabakh was an enclave populated mostly, but not exclusively, by Armenians in the Transcaucasia republic of Azerbaijan. Relations between Armenians and Azerbaijanis had always been strained, with mutual claims dating back to the Ottoman Empire; Soviet administrative policy based purely on geography and economy only made things worse.

In spring 1989, nationalists took to the streets in another Transcaucasian republic — Georgia. The country was (and still is) comprised of many ethnic groups, each claiming a separate territory, sometimes as small as just one hill and a couple of villages, and the rise of nationalism there was even more dangerous. Georgians marched under slogans “Down with Communism!” and “Down with Soviet Imperialism.” The rallies were guarded and directed by the “Georgian Falcons” — a special team of strong men, many of them veterans of the Afghan war, armed with truncheons and steel bars.

“Down with Communism!”

“Down with Soviet Imperialism.”

This time Gorbachev chose not to wait for clashes and a Spetsnaz regiment was deployed to Tbilisi to tackle the nationalist rallies. Again, old Soviet methods mixed poorly with the realities of democratization. When the demonstrators saw the soldiers, they became more agitated, and the streets around the main flashpoints were blocked by transport and barricades. The soldiers were ordered to use only rubber truncheons and tear gas, and were not issued firearms, but facing the Georgian Falcons they pulled out the Spetsnaz weapon of choice — sharp shovels just as deadly as bayonets.

At least 19 people were killed in the clashes or trampled by the crowd that was forced from the central square but had nowhere to go. Hundreds were wounded.

AFP PHOTO.

Moscow ordered an investigation into the tragedy and a special commission uncovered many serious mistakes made both by the regional and central authorities and party leaders. However, at the May Congress of People’s Deputies, Gorbachev categorically refused to accept any responsibility for the outcome of the events in Tbilisi and blamed the casualties on the military.

Further on, the last Soviet leader persisted in the kind of stubbornness that inevitably must have played a part in his fall. In February 1990, the Communist Party’s Central Committee voted to adopt the presidential system of power and General Secretary Gorbachev became the first and last president of the USSR. The same plenum dismantled the Communist Party’s monopoly of power, even though the country had no grassroots political organizations or any political organizations not dependent on the communists save for the nationalists. As a result, the urge for succession increased rapidly, both in the regional republics and even in the Soviet heartland — the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic.

In 1990, the Republic of Lithuania was the first to declare independence from the Soviet Union. Despite his earlier promises, Gorbachev refused to recognize this decision officially. The region found itself in legal and administrative limbo and the Lithuanian parliament addressed foreign nations with a request to hold protests against “Soviet Occupation.”

In January 1991, the Lithuanian government announced the start of economic reforms with liberalization of prices, and immediately after that the Supreme Soviet of the USSR sent troops to the republic, citing “numerous requests from the working class.” Gorbachev also demanded Lithuania annul all new regulations and bring back the Soviet Constitution. On January 11, Soviet troops captured many administrative buildings in Vilnius and other Lithuanian cities, but the parliament and television center were surrounded by a thousand-strong rally of protesters and remained in the hands of the nationalist government. In the evening of January 12, Soviet troops, together with the KGB special purpose unit, Alpha, stormed the Vilnius television center, killing 12 defenders and wounding about 140 more. The troops were then called back to Russia and the Lithuanian struggle for independence continued as before.

AFP PHOTO.

Vilnius residents gather in front of the Lithuanian parliament following the takeover of the Radio and Television installations by Soviet troops.

AFP PHOTO.An armed unidentified man guards the Lithuanian parliament on January 19, 1991 in Vilnius.

AFP PHOTO.Vilnius residents holding a Lithuanian flag guard a barricade in front of the Lithuanian parliament on January 20, 1991.

AFP PHOTO.Soviet paratroopers charge Lithuanian demonstrators at the entrance of the Lithuanian press printing house in Vilnius. January, 1991.

AFP PHOTO.

Gorbachev again denied any responsibility, saying that he had received reports about the operation only after it ended. However, almost all members of the contemporary Soviet cabinet recalled that the idea of Gorbachev not being aware of such a major operation was laughable. Trying to shift the blame put the president’s image into a lose-lose situation — knowing about the Vilnius fighting made him a callous liar, and if he really knew nothing about it, then he was an ineffective leader, losing control both of distant territories and his own special forces.

The swiftly aborted intervention — troops were called back on the same day — was a disappointment both to the hardliners, who would have wanted Gorbachev to see it through, and to the democratic reformers, horrified by the scenes emerging from Vilnius.

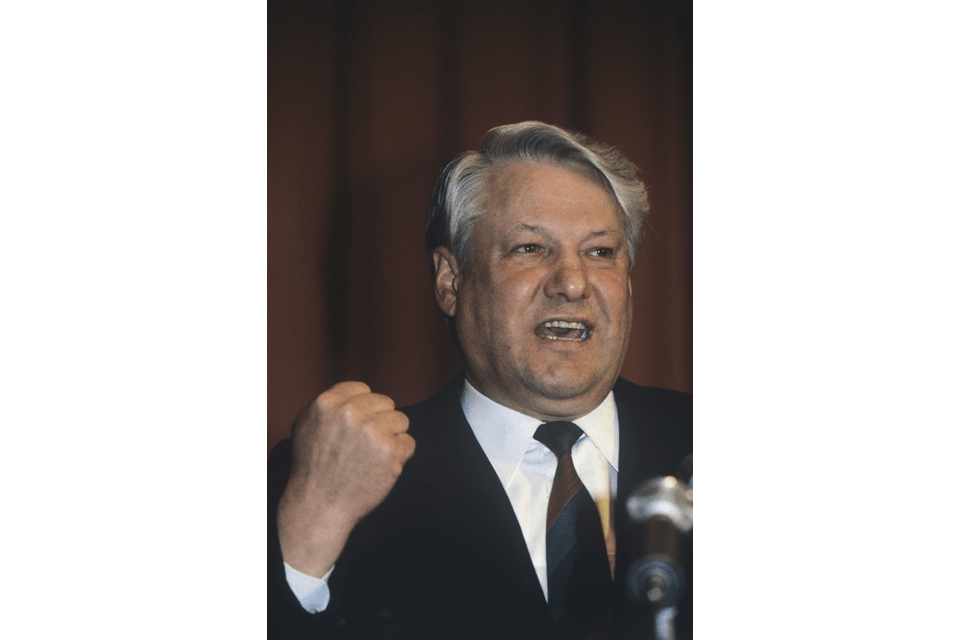

This dissatisfaction also must be one of the main factors that provoked the so-called Putch in August 1991 — an attempt by die-hard Politburo members to displace Gorbachev and restore the old Soviet order. They failed in the latter, but succeeded in the former as Gorbachev, isolated at his government Dacha in Crimea, returned to Moscow only because of the struggles of the new Russian leader Boris Yeltsin. When Gorbachev returned, his power was so diminished that he could do nothing to prevent the Belovezha agreement — the pact between Russia, Belarus and Ukraine that ended the history of the Soviet Union and introduced the Commonwealth of Independent States. All republics became independent whether they were ready to or not.

This move, while granting people freedom from Soviet rule, also triggered a sharp rise in extreme nationalist activities — the stakes were high enough and whole nations were up for grabs. Also, in the three years between Gorbachev’s offering of freedom and the collapse of the USSR, nothing was done to calm simmering ethnic hatred, and with no directions from Moscow or control on the part of the Soviet police and army, many regions became engulfed in full-scale civil wars, based on ethnic grounds.

Things turned especially nasty in Tajikistan, where fighting between Iranian-speaking Tajiks and Turkic-speaking Uzbeks very soon led to ethnic cleansing. Refugees had to flee for their lives to Afghanistan, which itself witnessed a war between the Taliban and the Northern Alliance.

AFP PHOTO.

Two fighters of the Tajik pro-Communist forces engage in a battle with pro-Islamic fighters 22 December 1992 in a village some 31 miles from the Tajik capital of Dushanbe.

AFP PHOTO.Tajik women cry over the dead body of a soldier 29 January 1993. The soldier was killed during fighting between Tajikistan government troops and opposition forces in Parkhar.

AFP PHOTO.

The long and bloody war in Georgia also had a significant ethnic component. After it ended three regions that were part of the republic during Soviet times — Abkhazia, Adzharia and South Ossetia – declared independence, which was enforced by a CIS peacekeeping force. At some point, Georgia managed to return Adzharia but when Georgian President Mikhail Saakashvili, backed and armed by Western nations, attempted to capture South Ossetia in 2008, Russia had to intervene and repel the aggression. Subsequently, Russia recognized South Ossetia and Abkhazia as independent nations.

YELTSIN’S CHALLENGE

New star steals limelight

As Stalin and Trotsky, or Tony Blair and Gordon Brown could attest, your own archrival in politics is often on your team, pursuing broadly similar — but not identical aims — and hankering for the top seat.

But unlike those rivalries, the scenes in the fallout between Mikhail Gorbachev, and his successor, Boris Yeltsin played out not through backroom deals and media leaks, but in the form of an epic drama in front of a live audience of thousands, and millions sat in front of their televisions.

The two leaders were born a month apart in 1931, and followed broadly similar paths of reformist regional commissars – while Gorbachev controlled the agricultural Stavropol, Yeltsin attempted to revitalize the industrial region of Sverdlovsk, present-day Yekaterinburg.

Yet, Yeltsin was a definitely two steps behind Gorbachev on the Soviet career ladder, and without his leg-up might have never made it to Moscow at all. A beneficiary of the new leader’s clear out, though not his personal protégé, Yeltsin was called up to Moscow in 1985, and the following year, was assigned the post of First Secretary of the Moscow Communist Party, effectively becoming the mayor of the capital.

Yeltsin’s style dovetailed perfectly with the new agenda, and his superior’s personal style, though his personal relationship with Gorbachev was strained almost from the start. Breaking off from official tours of factories, the city administrator would pay surprise visits to queue-plagued and under-stocked stores (and the warehouses where the consumables were put aside for the elites); occasionally abandoning his bulletproof ZIL limo, Yeltsin would ride on public transport. This might appear like glib populism now, but at the time was uncynically welcomed. In the first few months in the job, the provincial leader endeared himself to Muscovites — his single most important power base in the struggles that came, and a guarantee that he would not be forgotten whatever ritual punishments were cast down by the apex of the Communist Party.

RIA Novosti.

Boris Yeltsin, left, candidate member of the Politburo of the CPSU Central Committee, at lunch.

RIA Novosti.Voters’ meeting with candidate for deputy of the Moscow Soviet in the 161st constituency, First Secretary of the CPSU Moscow Town Committee, Chairman of the USSR Supreme Soviet, Boris Yeltsin, centre.

RIA Novosti.People’s deputy Boris Yeltsin. Algirdas Brazauskas (right) and chairman of the Presidium of the USSR Supreme Council Mikhail Gorbachev on the presidium.

RIA Novosti.

But Yeltsin was not just a demagogue content with cosmetic changes and easy popularity, and after months of increasing criticism of the higher-ups, he struck.

During a public session of the Central Committee of the Communist Party in October 1987, the newcomer delivered a landmark speech.

In front of a transfixed hall, he told the country’s leaders that they were putting road blocks on the road to Perestroika, he accused senior ministers of becoming “sycophantic” towards Gorbachev. As his final flourish, Yeltsin withdrew himself from his post as a candidate to the Politburo — an unprecedented move that amounted to contempt towards the most senior Soviet institution.

The speech, which he later said he wrote “on his lap” while sitting in the audience just a few hours earlier, was Yeltsin in a nutshell. Unafraid to challenge authority and to risk everything, with a flair for the dramatic, impulsive and unexpected decision (his resignation as Russian president in his New Year’s speech being the most famous).

Footage shows Gorbachev looking on bemused from above. He did not publicly criticize Yeltsin there and then, and spoke empathetically about Yeltsin’s concerns, but later that day (with his backing) the Central Committee declared Yeltsin’s address “politically misguided”, a slippery Soviet euphemism that cast Yeltsin out into the political wilderness.

Gorbachev thought he had won the round — “I won’t allow Yeltsin anywhere near politics again” he vowed, his pique shining through — but from then on, their historical roles and images were cast.

Gorbachev, for all of his reforms, now became the tame, prissy socialist. Yeltsin, the careerist who nearly had it all, and renounced everything he had achieved at the age of 54 and re-evaluated all he believed in. Gorbachev, the Politburo chief who hid behind the silent majority, Yeltsin the rebel who stood up to it. Gorbachev, the politician who spoke a lot and often said nothing, Yeltsin, the man of action.

Historically, the contrast may seem unfair, as both were equally important historical figures, who had a revolutionary impact for their time. But stood side-by-side, Yeltsin — with his regal bearing and forceful charisma — not only took the baton of Perestroika’s promises, but stole the man-of-the-future aura that had hitherto belonged to Gorbachev, who now seemed fidgety and weaselly by comparison.

While he was stripped of his Moscow role, Yeltsin’s party status was preserved. This had a perverse effect. No one stopped Yeltsin from attending high-profile congresses. No one prevented him from speaking at them. It was the perfect situation — he had the platform of an insider, and the kudos of an outsider. Tens of deputies would come and criticize the upstart, and then he’d take the stage, Boris Yeltsin vs. The Machine.

On June 12, 1990 Russia declared sovereignty from the USSR. A month later, Yeltsin staged another one of his dramatic masterclasses, when he quit the Communist Party on-stage during its last ever national congress, and walked out of the cavernous hall with his head held high, as loyal deputies jeered him.

In June 1991, after calling a snap election, Yeltsin became the first President of Russia, winning 57 percent — or more than 45 million votes. The Party’s candidate garnered less than a third of Yeltsin’s tally.

By this time Gorbachev’s position had become desperate. The Soviet Union was being hollowed out, and Yeltsin and the other regional leaders were now actively colluding with each other, signing agreements that bypassed the Kremlin.

The Communists and nationalists — often one and the same — had once been ambivalent about Gorbachev’s reforms, and anyway had been loath to criticize their leader. But inspired by Gorbachev’s glasnost, and with the USSR’s long term prospects becoming very clear, they now wanted their say as well. A reactionary media backlash started against him, generals pronounced warnings of “social unrest” that sounded more like threats, and some had begun to go as far as to earnestly speculate that Gorbachev was working for the Cold War “enemy.”

USSR IMPLODES

Failed coup brings down faded leader of fractured country

The junta that tried to take power in the Soviet Union on the night of August 18th is one of the most inept in the history of palace coups.

On August 18, all phones at Gorbachev’s residence, including the one used to control the USSR’s nuclear arsenal, were suddenly cut off, while unbeknownst to him, a KGB regiment was surrounding the house. Half an hour later a delegation of top officials arrived at the residence in Foros, Crimea, walked past his family to his office, in their briefcases a selection of documents for Gorbachev to sign. In one scenario, he would simply declare a state of emergency, and proclaim control over all the rebel republics, in another he would hand over power to his deputy Gennady Yanaev, due to worsening health.

Genuinely angry at their disloyalty, the Soviet leader called them “chancers”, and refused to sign anything, saying he would not have blood on his hands. He then showed them out of the house with a lengthy tirade — clearly recollected by all present in their memoirs — in which he crowned the plotters a “bunch of cocks.”

The plotters were not prepared for this turn of events. Gathering once again back in Moscow, they sat around looking at their unsigned emergency decree, arguing and not daring to put their names on the typewritten document. As midnight passed, and more and more bottles of whisky, imported from the decadent West they were saving the USSR from, was brought in, the patriots found their courage, or at least persuaded Yanaev to place himself at the top of the list of signatories. The Gang of Eight would be known as the State Committee on the State of Emergency. Accounts say that by the time they were driven to their dachas — hours before the most important day of their lives — the plotters could barely stand. Valentin Pavlov, he of the unpopular monetary reform, and the prime minister, drank so much he had to be treated for acute alcohol intoxication, and was hospitalized with cardiac problems as the events of the next three days unfolded.

But orders were issued, and on the morning of the 19th tanks rolled into Moscow. While news suggested that nothing had gone wrong — and at this point it hadn’t — the junta made it seem as if everything had. Not only were there soldiers on street, but all TV channels were switched off, with Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake iconically played on repeat. By four o’clock in the afternoon, most of the relatively independent media was outlawed by a decree.

But for all their heavy-handed touch the putsch leaders did nothing to stop their real nemesis. Unlike most coups, which are a two-way affair, this was a triangular power struggle – between Gorbachev, the reactionaries, and Yeltsin. Perhaps, like Gorbachev, stuck in their mindset of backroom intrigue the plotters seemed to underrate Yeltsin, and the resources at his disposal.

Russia’s next leader had arrived in Moscow from talks with his Kazakhstan counterpart, allegedly in the same merry state as the self-appointed plotters. But when his daughter woke him up with news of the unusual cross-channel broadcasting schedule, he acted fast, and took his car straight to the center of Moscow. The special forces soldiers placed around his dacha by the conspirators were not ordered to shoot or detain him.

Yeltsin’s supporters first gathered just a few hundred yards from the Kremlin walls, and then on instruction marched through the empty city to the White House building, the home of the rebellious Russian parliament. There, in his defining moment and as the crowd (although at this early hour it was actually thinner than the mythology suggests) chanted his name, Yeltsin climbed onto the tank, reclaimed from the government forces, and loudly, without the help of a microphone, denounced the events of the past hours as a “reactionary coup.” In the next few hours, people from across Moscow arrived, as the crowd swelled to 70,000. A human chain formed around the building, and volunteers began to build barricades from trolleybuses and benches from nearby parks.

RIA Novosti.

RIA Novosti.

Moscow residents building barricades next to the Supreme Soviet during the coup by the State EmergencyCommittee.

RIA Novosti.Thousands of people rallying before the Supreme Soviet of Russia on August 20, 1991.

RIA Novosti.

Though this seemed as much symbolic, as anything, as the elite units sent in by the junta had no intention of shooting, and demonstrated their neutrality, freely mingling with the protesters. Their commander, Pavel Grachev, defected to Yeltsin the following day, and was later rewarded with the defense minister’s seat. The Moscow mayor Yuri Luzhkov also supported Yeltsin.

Reuters.

Realizing that their media blackout was not working, and that they were quickly losing initiative, the plotters went to the other extreme, and staged an unmoderated televised press conference.

Sat in a row, the anonymous, ashen-faced men looked every bit the junta. While Yanaev was the nominal leader, he was never the true engine of the coup, which was largely orchestrated by Vladimir Kryuchkov, the KGB chief, who, with the natural caution of a security agent, did not want to take center stage. The acting president, meanwhile, did not look the part. His voice was tired and unsure, his hands shaking — another essential memory of August 1991.

RIA Novosti.

RIA Novosti.

In another spectacularly poor piece of communications management, after the new leaders made their speeches, they opened the floor to an immediately hostile press pack, which openly quoted Yeltsin’s words accusing them of overthrowing a legitimate government on live television.

Referring to Gorbachev as “my friend Mikhail Sergeevich,” Yanaev monotoned that the president was “resting and taking a holiday in Crimea. He has grown very weary over these last few years and needs some time to get his health back.” With tanks standing outside proceedings were quickly declining into a lethargic farce in front of the whole country.

Over the next two days there was international condemnation (though Muammar Gaddafi, Saddam Hussein and Yasser Arafat supported the coup) the deaths of three pro-Yeltsin activists, and an order by the junta to re-take the White House at all costs, canceled at the last minute. But by then the fate of the putsch had already been set in motion.

Meanwhile, as the most dramatic events in Russia since 1917 were unfolding in Moscow, Gorbachev carried on going for dips in the Black Sea, and watching TV with his family. On the first night of the coup, wearing a cardigan not fit for an nationwide audience, he recorded an uncharacteristically meek address to the nation on a household camera, saying that he had been deposed. He did not appear to make any attempt to get the video out of Foros, and when it was broadcast the following week, it incited reactions from ridicule, to suspicions that he was acting in cahoots with the plotters, or at least waiting out the power struggle in Moscow. Gorbachev likely was not, but neither did he appear to exhibit the personal courage of Yeltsin, who came out and addressed crowds repeatedly when a shot from just one government sniper would have been enough to end his life.

On the evening of August 21, with the coup having evidently failed, two planes set out for Crimea almost simultaneously from Moscow. In the first were the members of the junta, all rehearsing their penances, in the other, members of Yeltsin’s team, with an armed unit to rescue Gorbachev, who, for all they knew, may have been in personal danger. When the putschists reached Foros, Gorbachev refused to receive them, and demanded that they restore communications. He then phoned Moscow, Washington and Paris, voiding the junta’s decrees, and repeating the simple message: “I have the situation under control.”

But he did not. Gorbachev’s irrelevance over the three days of the putsch was a metaphor for his superfluousness in Russia’s political life in the previous months, and from that moment onward. Although the putschists did not succeed, a power transfer did happen, and Gorbachev still lost. For three days, deference to his formal institutions of power was abandoned, and yet the world did not collapse, so there was no longer need for his dithering mediation.

Gingerly walking down the steps of the airstair upon landing in Moscow, blinking in front of the cameras, Mikhail Gorbachev was the lamest of lame duck leaders. He gave a press conference discussing the future direction of the Communist Party, and inner reshuffles that were to come, sounding not just out-of-touch, but borderline delusional.

Reuters.

Reuters.

Gorbachev resigned as the President of the Soviet Union on December 25, 1991.

“The policy prevailed of dismembering this country and disuniting the state, which is something I cannot subscribe to,” he lamented, before launching into an examination of his six years in charge.

“Even now, I am convinced that the democratic reform that we launched in the spring of 1985 was historically correct. The process of renovating this country and bringing about drastic change in the international community has proven to be much more complicated than anyone could imagine.”

“However, let us give its due to what has been done so far. This society has acquired freedom. It has been freed politically and spiritually, and this is the most important achievement that we have yet fully come to grips with.”

AFTERMATH

Praised in West, scorned at home

“Because of him, we have economic confusion!”

“Because of him, we have opportunity!”

“Because of him, we have political instability!”

“Because of him, we have freedom!”

“Complete chaos!”

“Hope!”

“Political instability!”

“Because of him, we have many things like Pizza Hut!”

Thus ran the script to the 1997 advert that saw a tableful of men argue loudly over the outcome of Perestroika in a newly-opened Moscow restaurant, a few meters from an awkward Gorbachev, staring into space as he munches his food alongside his 10 year-old granddaughter. The TV spot ends with the entire clientele of the restaurant getting up to their feet, and chanting “Hail to Gorbachev!” while toasting the former leader with pizza slices heaving with radiant, viscous cheese.

The whole scene is a travesty of the momentous transformations played out less than a decade earlier, made crueler by contemporary surveys among Russians that rated Gorbachev as the least popular leader in the country’s history, below Stalin and Ivan the Terrible.

The moment remains the perfect encapsulation of Gorbachev’s post-resignation career.

To his critics, many Russians among them, he was one of the most powerful men in the world reduced to exploiting his family in order to hawk crust-free pizzas for a chain restaurant — an American one at that — a personal and national humiliation, and a reminder of his treason. For the former Communist leader himself it was nothing of the sort. A good-humored Gorbachev said the half-afternoon shoot was simply a treat for his family, and the self-described “eye-watering” financial reward — donated entirely to his foundation — money that would be used to go to charity.

As for the impact of Gorbachev’s career in advertising on Russia’s reputation… In a country where a decade before the very existence of a Pizza Hut near Red Square seemed unimaginable, so much had changed, it seemed a perversely logical, if not dignified, way to complete the circle. In the years after Gorbachev’s forced retirement there had been an attempted government overthrow that ended with the bombardment of parliament, privatization, the first Chechen War, a drunk Yeltsin conducting a German orchestra and snatching an improbable victory from revanchist Communists two years later, and an impending default.

Although he did get 0.5 percent of the popular vote during an aborted political comeback that climaxed in the 1996 presidential election, Gorbachev had nothing at all to do with these life-changing events. And unlike Nikita Khrushchev, who suffered greater disgrace, only to have his torch picked up, Gorbachev’s circumstances were too specific to breed a political legacy. More than that, his reputation as a bucolic bumbler and flibbertigibbet, which began to take seed during his final years in power, now almost entirely overshadowed his proven skill as a political operator, other than for those who bitterly resented the events he helped set in motion.

Other than in his visceral dislike of Boris Yeltsin — the two men never spoke after December 1991 — if Gorbachev was bitter about the lack of respect afforded to him at home, he wore it lightly. Abroad, he reveled in his statesmanlike aura, receiving numerous awards, and being the centerpiece at star-studded galas. Yet, for a man of his ambition, being pushed into retirement must have gnawed at him repeatedly.

After eventually finding a degree of financial and personal stability on the lecture circuit in the late 1990s, Gorbachev was struck with another blow — the rapid death of Raisa from cancer.

A diabetic, Gorbachev became immobile and heavy-set, a pallor fading even his famous birthmark. But his voice retained its vigor (and accent) and the former leader continued to proffer freely his loquacious opinions on politics, to widespread indifference.

Gorbachev’s legacy is at the same time unambiguous, and deeply mixed — more so than the vast majority of political figures. His decisions and private conversations were meticulously recorded and verified. His motivations always appeared transparent. His mistakes and achievements formed patterns that repeated themselves through decades.

Yet for all that clarity, the impact of his decisions, the weight given to his feats and failures can be debated endlessly, and has become a fundamental question for Russians.

Less than three decades after his limo left the Kremlin, his history has been rewritten several times, and his role bent to the needs of politicians and prevailing social mores. This will likely continue. Those who believe in the power of the state, both nationalists and Communists, will continue to view his time as egregious at best, seditious at worst. For them, Gorbachev is inextricably linked with loss — the forfeiture of Moscow’s international standing, territory and influence. The destruction of the fearsome and unique Soviet machine that set Russia on a halting course as a middle-income country with a residual seat in the UN Security Council trying to gain acceptance in a US-molded world.

Others, who appreciate a commitment to pacifism and democracy, idealism and equality, will also find much to admire in Gorbachev, even though he could not always be his best self. Those who place greater value on the individual than the state, on freedom than on military might, those who believe that the collapse of the Iron Curtain and the totalitarian Soviet Union was a landmark achievement not a failure will be grateful, and if not sympathetic. For one man’s failure can produce a better outcome than another’s success.

RAISA

Passion and power

The history of rulers is littered with tales of devoted wives and ambitious women pulling strings from behind the throne, and Raisa was often painted as both. But unlike many storybook partnerships, where the narrative covers up the nuances, the partnership between Mikhail and Raisa was absolutely authentic, and genuinely formidable. Perhaps the key to Mikhail’s lifelong commitment, and even open deference to his wife, atypical for a man of his generation, lay in their courtship.

In his autobiography, Gorbachev recollects with painful clarity, how his first meeting with Raisa, on the dance floor of a university club, “aroused no emotion in her whatsoever.” Yet Gorbachev was smitten with the high cheek-boned fellow over-achiever immediately, calling her for awkward dorm-room group chats that went nowhere, and seeking out attempts.

— Raisa Gorbacheva

“We were happy then. We were happy because of our young age, because of the hopes for the future and just because of the fact that we lived and studied at the university. We appreciated that.”

It was several months before she agreed to even go for a walk through Moscow with the future Soviet leader, and then months of fruitless promenades, discussing exams at their parallel faculties. With candor, Gorbachev admits that she only agreed to date him after “having her heart broken by the man she had pledged it to.” But once their relationship overcame its shaky beginnings, the two became the very definition of a Soviet power couple, in love and ready to do anything for each other. In the summer vacation after the two began to go steady, Gorbachev did not think it below him to return to his homeland, and resume work as a simple mechanic, to top up the meager university stipend.

The two were not embarrassed having to celebrate their wedding in a university canteen, symbolically, on the anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution on November 7, 1953. Or put off when the watchful guardians of morality at Moscow State University forbid the newlyweds from visiting each other’s halls without a specially signed pass. More substantial obstacles followed, when Mikhail’s mother also did not take to her daughter-in-law, while Raisa agreed to a medically-advised abortion after becoming pregnant following a heavy bout of rheumatism. But the two persevered. Raisa gave birth to their only child in 1955, and as Gorbachev’s star rose, so did his wife’s academic career as a sociologist. But Raisa’s true stardom came when Gorbachev occupied the Soviet leader’s post.

RIA Novosti.

Raisa Gorbacheva, the wife of the Soviet leader (left), showing Nancy Reagan, first lady of the U.S., around the Kremlin during U.S. President Ronald Reagan’s official visit to the U.S.S.R.

RIA Novosti.General Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee Mikhail Gorbachev (center left) and his spouse Raisa Gorbacheva (second from left) seeing off US President Ronald Reagan after his visit to the USSR. Right: The spouse of US president Nancy Reagan. The Hall of St. George in the Grand Kremlin Palace.

RIA Novosti.Raisa Gorbacheva (left), wife of the general secretary of the Soviet Communist Party, and Barbara Bush (right), wife of the U.S. president, attending the inauguration of the sculptured composition Make Way for Ducklings near the Novodevichy Convent during U.S. President George Bush’s official visit to the U.S.S.R.

RIA Novosti.Soviet first lady Raisa Gorbacheva meets with Tokyo residents during Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachyov’s official visit to Japan.

RIA Novosti.The meeting between Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev, President of the USSR and the heads of state and government of the seven leading industrial nations. From left to right: Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev, Norma Major, Raisa Maksimovna Gorbacheva and John Major.

RIA Novosti.Soviet president’s wife Raisa Gorbacheva at the 112th commencement at a female college. The State of Massachusetts. Soviet president Mikhail Gorbachev’s state visit to the United States.

RIA Novosti.

In a symbol as powerful as his calls for international peace and reform at home, the Communist leader was not married to a matron hidden at home, but to an urbane, elegantly-dressed woman, regarded by many as an intellectual equal, if not superior to Mikhail himself. Gorbachev consulted his wife in every decision, as he famously told American TV viewers during a Tom Brokaw interview. This generated much ill-natured mockery throughout Gorbachev’s reign, but he never once tried to push his wife out of the limelight, where she forged friendships with such prominent figures as Margaret Thatcher, Nancy Reagan and Barbara Bush.

Raisa was there in the Crimean villa at Foros, during the attempted putsch of August 1991, confronting the men who betrayed her husband personally, and suffering a stroke as a result. It was also Raisa by Gorbachev’s side when they were left alone, after the whirlwind settled in 1991. Despite nearly losing her eyesight due to her stroke, Raisa largely took the lead in organizing Mikhail’s foundation, and in structuring his life. In 1999, with his own affairs in order, not least because of the controversial Pizza Hut commercial, and Russians anger much more focused on his ailing successor, Gorbachev thought he could enjoy a more contented retirement, traveling the world with his beloved.

RIA Novosti.

Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev (center), Soviet first lady Raisa Gorbacheva (right), Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbayev and Kazakh first lady Sara Nazarbayeva during Gorbachev’s working visit to Kazakhstan.

RIA Novosti.General Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee Mikhail Gorbachev (left) and his spouse Raisa Gorbachev (center) at a friendship meeting in the Wawel Castle during a visit to Poland.

RIA Novosti.Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev and his wife Raisa during his official visit to China.

RIA Novosti.An official visit to Japan by USSR President Mikhail Gorbachev. He with wife, Raisa Gorbachev, and Japanese Prime Minister Toshiki Kaifu near a tree planted in the garden of Akasaka Palace.

RIA Novosti.Mikhail Gorbachev (center), daughter Irina (right) and his wife’s sister Lyudmila (left) at the funeral of Raisa Gorbachev.

RIA Novosti.Last respects for Raisa Gorbacheva, spouse of the former the USSR president in the Russian Fond of Culture. Mikhail Gorbachev, family and close people of Raisa Gorbacheva at her coffin.

RIA Novosti.Mikhail Gorbachev at the opening of the Raisa exhibition in memory of Raisa Gorbacheva.

RIA Novosti.

— Raisa Gorbacheva

“It is possible that I had to get such a serious illness and die for the people to understand me.”

Then came the leukemia diagnosis, in June of that year. Before the couple’s close family had the chance to adjust to the painful rhythm of hope and fear that accompanies the treatment of cancer, Raisa was dead. Her burial unleashed an outpouring of emotion, with thousands, including many of her husband’s numerous adversaries, gathering to pay their sincere respects. No longer the designer-dressed careerist ice queen to be envied, resented and ridiculed, now people saw Raisa for the charismatic and shrewd idealist she always was. For Gorbachev it made little difference, and all those around him said that however much activity he tried to engage in following his wife’s death, none of it ever had quite the same purpose.

“People say time heals. But it never stops hurting – we were to be joined until death,” Gorbachev always said in interviews

For the tenth anniversary of Raisa’s death, in 2009, Mikhail Gorbachev teamed up with famous Russian musician Andrey Makerevich to record a charity album of Russian standards, dedicated to his beloved wife. The standout track was Old Letters, a 1940s melancholy ballad. Gorbachev said that it came to him in 1991 when he discovered Raisa burning their student correspondence and crying, after she found out that their love letters had been rifled through by secret service agents during the failed coup.

The limited edition LP sold at a charity auction in London, and fetched £100,000.

Afterwards, Gorbachev got up on the stage to sing Old Letters, but half way through he choked up, and had to leave the stage to thunderous applause.

Filed under: Afghanistan, East Eurpoe, Russia, US-Russia Relations, USSR | Tagged: Belarus, cold war, Collapse of USSR, Communism, Georgia, Gorbachev, KGB, Lithuania, Margret Thatcher, Nationalism, PERESTROIKA, Proxy War, Ronald Reagan, Yeltsin | Comments Off on ‘If not me, who?’: Mikhail Gorbachev ended Cold War and saved the world, but failed to save Soviet Union FEATURE